Brief History of Positive Psychology (Part 2)

Continued From Part 1...

But Wait, There is Good News

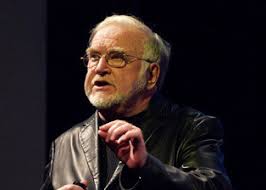

Remember, Csikszentmihalyi found that teenagers can be unhappy and can see life through their suffering, but he also found an interesting exception. When teenagers focus their energies on tasks that are challenging, their mood is more upbeat. In other words, he found evidence of when teenagers move away from a negative focus and begin to experience positive emotions. This formed the basis for his work on the concept of flow.

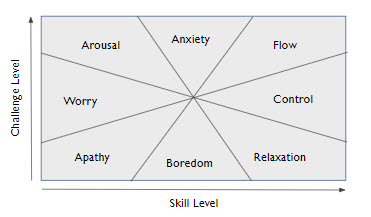

Flow is the opposite of apathy. It is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, merely for the sake of doing it. Flow occurs when we use our highest strengths and skills at a level that challenges us at our peak level causing a gestalt of sorts where the sum of our efforts are multiplied because of how smoothly everything is working together. If our activity does not use our strengths or skills at a high level, we can get bored more easily. If we are not challenged we may move toward relaxation and away from flow.

Flow is the opposite of apathy. It is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, merely for the sake of doing it. Flow occurs when we use our highest strengths and skills at a level that challenges us at our peak level causing a gestalt of sorts where the sum of our efforts are multiplied because of how smoothly everything is working together. If our activity does not use our strengths or skills at a high level, we can get bored more easily. If we are not challenged we may move toward relaxation and away from flow.

Research has discovered a neurological connection between flow and time in that during flow, the frontal lobe is shut down, a concept known as transient hypofrontality (Dietrich, 2006). Perhaps this allows us to avoid cognitive distractions that prevent us from being in the moment and our brains are freed up for more creative work.

After witnessing many people struggle after WWII, Csikszentmihalyi wondered about those who seemed to thrive despite their circumstances. He began to research the strengths that people have that help them overcome adversity. This work and the concept of Flow have become an integral part of the history and development of Positive Psychology. Csikszentmihalyi famously said, 'The best moments in our lives . . . occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.' In 2009, Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi was awarded the Strengths Prize from APA, named in honor of Donald Clifton.

After witnessing many people struggle after WWII, Csikszentmihalyi wondered about those who seemed to thrive despite their circumstances. He began to research the strengths that people have that help them overcome adversity. This work and the concept of Flow have become an integral part of the history and development of Positive Psychology. Csikszentmihalyi famously said, 'The best moments in our lives . . . occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.' In 2009, Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi was awarded the Strengths Prize from APA, named in honor of Donald Clifton.

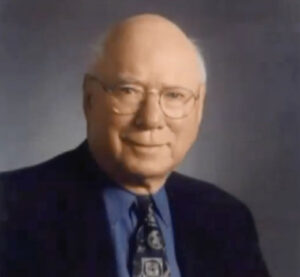

Donald Clifton was a WWII veteran and an educational psychologist who asked a simple question that many argue gave birth to the positive psychology movement in the late 1950s and early 60s: What will happen when we think about what is right with other people rather than fixating on what is wrong with them? He studied what made people successful rather than what happened to cause them to fail and this research eventually led to the development of his Strengths Theory. He wrote several bestsellers related to identifying and maximizing strengths, including his most famous book, Now, Discover Your Strengths, and he developed the Clifton Strengthsfinder, the most commonly used strength assessment, used mostly in educational and organizational environments.

Donald Clifton was a WWII veteran and an educational psychologist who asked a simple question that many argue gave birth to the positive psychology movement in the late 1950s and early 60s: What will happen when we think about what is right with other people rather than fixating on what is wrong with them? He studied what made people successful rather than what happened to cause them to fail and this research eventually led to the development of his Strengths Theory. He wrote several bestsellers related to identifying and maximizing strengths, including his most famous book, Now, Discover Your Strengths, and he developed the Clifton Strengthsfinder, the most commonly used strength assessment, used mostly in educational and organizational environments.

In 2003, Donald Clifton was awarded The Presidential Commendation from the American Psychological Association or his lifetime achievements in 'living out the vision that life and work could be about building what is best and highest, not just about correcting weakness,' the commendation calls him the father of strengths-based psychology and the grandfather of positive psychology.

Martin Seligman Moves us from Helpless to Optimistic

As Clifton was asking what makes us successful, Seligman was focused on the opposite. He was researching learned helplessness and our natural state of pessimism. He would later say that we got it wrong, that focusing on the bad stuff made things worse and if we could learn to be helpless, could we also learn to be optimistic. His book, Learned Optimism, was published in 1990 and marked his transition from a regular pessimist to an optimistic pessimist.

As Clifton was asking what makes us successful, Seligman was focused on the opposite. He was researching learned helplessness and our natural state of pessimism. He would later say that we got it wrong, that focusing on the bad stuff made things worse and if we could learn to be helpless, could we also learn to be optimistic. His book, Learned Optimism, was published in 1990 and marked his transition from a regular pessimist to an optimistic pessimist.

Seligman was elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1998 and put the weight of his office behind positive psychology, pushing it to the forefront in the psychology world. As APA president, he argued that psychology was “half-baked” because we only focused on the pessimistic half of human existence. He famously stated, 'If all you do is work to fix problems, to alleviate suffering, then by definition you are working to get people to zero, to neutral.'

Seligman was elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1998 and put the weight of his office behind positive psychology, pushing it to the forefront in the psychology world. As APA president, he argued that psychology was “half-baked” because we only focused on the pessimistic half of human existence. He famously stated, 'If all you do is work to fix problems, to alleviate suffering, then by definition you are working to get people to zero, to neutral.'

While he still believes that pessimism is a more natural state for us as humans, he is now quick to point out that by recognizing and developing our strengths rather than focusing purely on our weaknesses, we can overcome pain and can work toward well-being. And by adding resilience to the mix, we are more able to prevent the back swing of life’s pendulum and continue to move forward toward well-being and away from pain. These two concepts, increasing well-being and building resilience, have become the cornerstone of positive psychotherapy and other strengths-based approaches.

Which brings us back to Schopenhauer, and life’s pendulum that swings backward and forward between pain and boredom. Remember, Seligman called psychology half-baked because we typically focus only on pain in our work with clients. This was especially true for clinical psychologists who are trained to assess, diagnose, and treat based on the medical model, or what is often referred to as the disease model.

Which brings us back to Schopenhauer, and life’s pendulum that swings backward and forward between pain and boredom. Remember, Seligman called psychology half-baked because we typically focus only on pain in our work with clients. This was especially true for clinical psychologists who are trained to assess, diagnose, and treat based on the medical model, or what is often referred to as the disease model.

What psychologists like Seligman have taught us is that the pendulum of human existence does indeed swing back and forth but not merely from pain to boredom. And from this we began to see the role of mental health treatment not only as a means to alleviate suffering but also as a way to increase well-being.

Positive Psychology, by definition, is the study of well-being. Is it not a therapy approach, but rather a theory that allows for the research and application of approaches that promote well-being. Well-being is not the same as happiness, although being happy is part of one of the areas identified by Seligman so happiness can be a part of well-being.

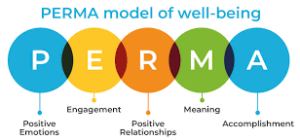

The PERMA Model

The Positive Psychology model of well-being consists of five areas where individuals, families, and communities can thrive. The more we thrive in each of these, the more resilient we are and the greater our reported sense of well-being. It is known as the PERMA Model of Well-Being.

The Positive Psychology model of well-being consists of five areas where individuals, families, and communities can thrive. The more we thrive in each of these, the more resilient we are and the greater our reported sense of well-being. It is known as the PERMA Model of Well-Being.

The first area is Positive emotions. Happiness would fit into this category, but so would joy, contentment, amusement, pride, inspiration, gratitude, satisfaction, relief, love, awe, and especially hope.

The second, Engagement, concerns our activities. How do we spend our time, what do we focus on? Csikszentmihalyi’s research on Flow fits here as the ultimate engagement. If you have experienced flow, then you have been able to successfully focus your values, strengths, and goals into a single activity that has monopolized your focus.

Relationships refer to our connections with others. Research has overwhelmingly demonstrated the importance of relationships in our mental health functioning and overall life satisfaction. But relationships need to be positive to increase well-being.

Meaning represents a focus or dedication to something bigger than ourselves. Finding meaning allows us to feel a part of something larger and gives our lives purpose. Meaning can be religious or spiritual, it can be about social justice, or family, or giving back to the community.

And finally, Accomplishment or Achievement. This is the sense of forward movement and productivity that we feel when we work toward a goal, get something done, when we contribute to something, when we feel we have created something important or meaningful. Having a sense of pride in what we do creates well-being and improves overall life-satisfaction. Angela Duckworth’s research on Grit fits nicely in this category.

Character Strengths and Resilience

The field of positive psychology continues to grow, spurred on by calls from the American Psychological Association, the American Counseling Association, and the National Association of Social Work to expand on the deficit model of mental health by adding a prominent strengths-based model. A lot of exciting new research and the development of new concepts has occurred in just the last ten or 15 years.

The field of positive psychology continues to grow, spurred on by calls from the American Psychological Association, the American Counseling Association, and the National Association of Social Work to expand on the deficit model of mental health by adding a prominent strengths-based model. A lot of exciting new research and the development of new concepts has occurred in just the last ten or 15 years.

Peterson and Seligman developed a model of character strengths and virtues and an assessment instrument that uses traditional psychological testing theory and approaches. Rather than identifying psychopathology or abnormal behavior, their instrument, known as the VIA Character Strengths Survey (https://www.viacharacter.org/), measures positive aspects of normal behavior. The free component of the survey takes about 20 minutes to complete and will rank order your strengths from most dominant to least dominant. The idea, which fits nicely in the strengths-based movement in mental health, is to build on strengths rather than merely reduce weaknesses.

Resilience is another topic that has received a great deal of attention in both the self-help arena and in academic and federally funded research. Resilience has become a component of positive psychology and has been included under the umbrella term Psychological Capital, which represents an individual’s base level of well-being. Psychological Capital includes Hope, Self-Efficacy, Resilience, and Optimism and is often referred to with the acronym HERO. This model was developed in the organizational psychology subfield but is being used more broadly today.

As we move forward, positive psychotherapy and other strengths-based interventions are showing promise and many established approaches to psychotherapy are adding strengths-based components. Technology is also being used to expand the reach of positive psychology and to continue Seligman’s original and ongoing vision of positive psychology as the scientific study of the strengths that enable individuals and communities to thrive. Psychology has truly undergone a significant paradigm shift and its future is looking positive.

References

Buckingham, M. & Clifton, D. O. Now, develop your strengths. The Free Press.

Dietrich, A. (2006). Transient hypofrontality as a global mechanism for the psychological effects of exercise. Psychiatry Research, 145(1), 79-83.

Frankl, V. (1946). Man's search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Troxell, M. (n.d.). Arthur Shopenhauer. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://www.iep.utm.edu/schopenh/.

VIA Institute on Character (n.d.). VIA Character Strengths Survey. Retrieved from https://www.viacharacter.org/).